Continuing The Journey of East African Dhows

Utamaduni dhow, in the process of being rebuilt at Ali’s workshop in Lamu | © Hannah Evans

Footprints in the sand | © Daniel Snyders

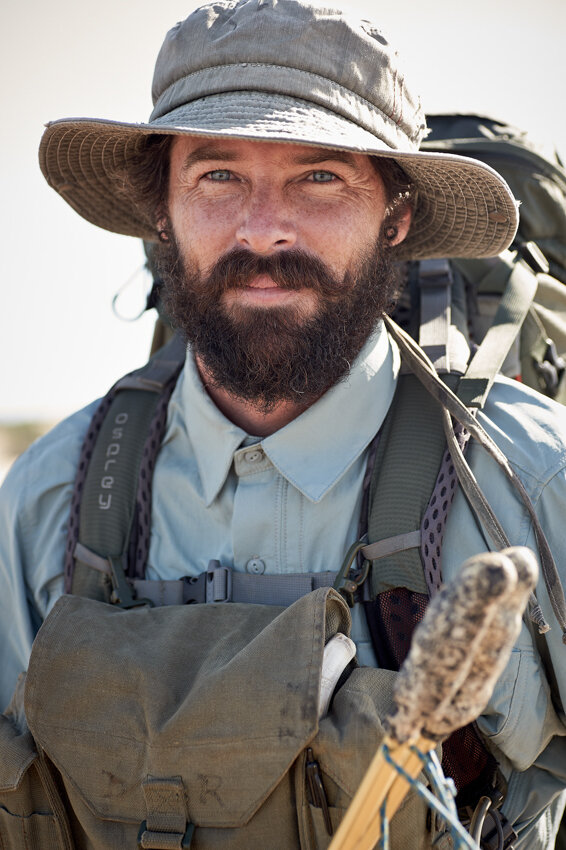

My backpack sits snuggly, like a saddle. Footsteps, rising and falling, thousands per day, some on soft sand, some on rock and some on the rolling grassy hills of the Xhosa homeland, Transkei.

I’m barefoot now and feeling strong. Walking always with the ocean on my right and the land on my left. I’ve weighed anchor on my life and set off, tracing the coastline from my home in Cape Town to Mozambique. Where, how, what and why I can’t answer I’m just going, driven north.

I’ve seen and heard a bit about dhows before and their majestic shapes and lines have enchanted me. A seed begins to take root and grow as I walk. Every now and then a tailwind picks up and I lift my arms like wings trying to catch it to help me on my way. There’s excitement there. Like the moments before take-off, like a fledgling not quite knowing how but called to use that wind to take flight and soar.

I yearn to sail!

Wouldn’t it be great to build a boat and continue the pilgrimage north…

A traditional dhow can’t be that hard to build I think to myself. As I enter Mozambique the first thing I find is dhows.

Dhows were used as vessels of trade and exploration. Enterprising Arabs sailed dhows down the coast of Africa some two thousand years ago. Finding Africa rich in resources they opened the world’s oldest commercial sailing route.

The orient grew rich on the backs of these majestic vessels. It saw the rise of the Arabic empire and legends such as Sindbad the sailor. The cultural spin-offs saw the development of the Swahili language and culture, a mix of all the languages the dhows visited along their way. Architecture, woodcarving, cuisine and people merged and flourished.

It wasn’t all roses though, slavery was one of the biggest exports and tribes as far as the Congo was preyed upon. The ivory trade was another key trade leading to the death of millions of elephants.

Daniel while on expedition up the coast of East Africa | © Daniel Snyders

Off I went in search of a dhow builder to help me knock one of these beauties together.

The more I dug the more I realized the practicalities of doing a long ocean voyage and what dhow building looks like today. And it wasn’t looking all that promising.

To find a good builder was long and eventful. First of all, if one wants to be safe at sea on one of these open decked vessels you need to be a bit higher off the water and that meant a bigger boat. Dhows today are used mostly locally and long voyages in them are hardly heard of.

Ibo an island in Mozambique last saw an ocean-going dhow leave their shores in the ’60s.

The world is changing and with higher import and export duties it’s not affordable for smaller vessels to trade across borders. Thus the rise of tankers and the boom dhows from Asia that are just clinging onto the last embers of this ancient trade route.

Another obstacle to the construction of dhows is resources. Hardwood timbers used are becoming increasingly rare and in some cases near extinct. The other is time, which in this day and age means money. Dhows take time, there’s no production line to put one of these beauties together.

Each piece of wood is selected and crafted by a master that works from no plans but the one in his head and hands.

The birth of a plastic revolution and the future of dhow building?

The entrance to The Flipflopi and Takataka Heroes workspace in Lamu | © Hannah Evans

Then came along a man called Ben Morison with an idea that pieced together the potential of all the plastic waste he saw along our beaches. Why not build a traditional dhow with plastic! He met Ali Skanda who was struggling with the same concerns, Dipesh Pabari an old friend of Ben’s and activist was brought in and a plastic revolution was born.

I suspect is that this could be a potential future offshoot of dhow construction. Give the trees a break and save on the costly materials needed to build dhows. Plastic is not as good as wood but using plastic waste to build dhows offers a solution to two problems.

And so my relationship with the Flipflopi began. I was able to meet one of the last dhow builders in Africa who still know how to build an ocean-going dhow.

Ali Skanda is in the process of restoring one of these ancients as we speak - Utamuduni meaning culture in Swahili.

Ali and the Flipflopi team are using Utamuduni as a blueprint for the building of Flipflopi kubwa. A 24 metre recycled plastic dhow capable of sailing the high seas spreading the plastic revolution!

Utamaduni belongs to Manda Bay and is one of Africa’s last remaining large dhows. She might not traverse the course her ancestors did and the skill and knowledge to build these giants will likely end with Ali and his contemporaries.

But what we can do is recognise the important role these large dhows played in the creation of the rich culture on the Eastern coast of Africa so we can take steps to preserve their heritage.

By creating these ancient vessels recycled plastics we can kill two birds with one stone.

Realise the value of this throwaway material.

By preserving these old skills we can remember where we came from.

Our journeys may never end but we can make sure they are pointed toward a good destination.

We have a YouTube channel where you can see the documenting of Utamaduni’s build which will roll out over the next few years. Alongside her, Flipflopi kubwa will also be built! We’re excited to have all this beautiful building action going on around. You can tap into some of the goings-on and the lead up to this fine introduction by following here.

The ribs of Utamaduni Dhow, each having been replaced by hand by Captain Ali | © Hannah Evans